Armchair travel around the world!

Start your reading adventures with our FREE Reading Atlas.

- Around the World in 14 Books

- 7 Thrilling Book Series

- 6 Audiobooks That Are Like Theater For Your Ears

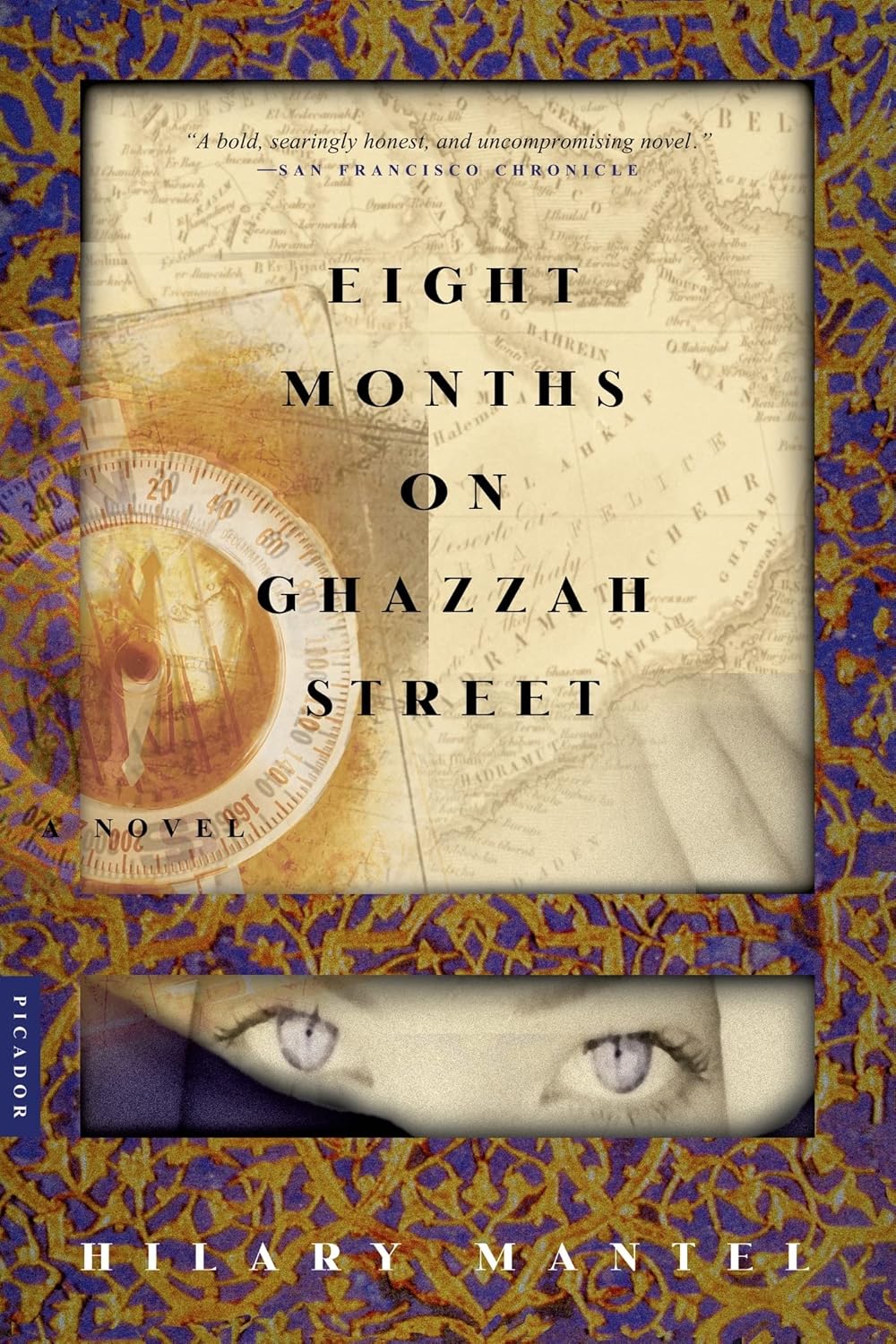

This Gothic-tinged novel (288 pages) was published in September of 2003 by Picador. The book takes you to 1980s Jeddah, Saudi Arabia. Melissa read Eight Months on Ghazzah Street and loved it; it wouldn't be on our site if she didn't recommend it.

Bookshop.org is an online bookstore with a mission to financially support independent bookstores and give back to the book community.

In this gripping (Gothic) novel, Hilary Mantel — author of the Wolf Hall trilogy — applies her storytelling skills to an account of eight months in the lives of a British couple, Andrew and Frances, expats in 1980s Jeddah, Saudi Arabia.

Mantel and her husband lived in the Kingdom for four years, and she was very frank about how much she disliked her time there. When asked about the happiest moment in her life, she replied, ‘Leaving Jeddah.’ While serving her time there, she kept detailed journals, and when she returned to the UK, she transformed those recollections into this novel.

The story opens with Frances flying to Jeddah for a reunion with her husband, an architect who’s already been working and living in Jeddah for a few months. From the first page, there’s a strong sense of foreboding, and the contradictions are already beginning: Passengers on the plane drink alcohol like it’s their job. Men across the aisle are nosy and flirt with Frances in an unsettling way. It’s loud, boisterous, wrong somehow. As they approach the airport, the steward remarks to Frances, ‘Listen, if anything goes wrong, if by some mischance hubby’s not there, don’t hang about, don’t speak to anybody, get straight in our airline bus and come downtown with us to the Hyatt Regency.’ When Frances protests that she can simply take a taxi, the steward replies, ‘You’re a woman, aren’t you? You’re not a person anymore.’

There’s little reassurance when Frances safely arrives inside the apartment rented for them by Andrew’s employer. One of the doors to the hallway has bricked up, and the other windows look out onto walls — all the better to keep the woman inside from being seen by people outside.

Her first full day on her own is a Gothic-tinged waking nightmare. When Andrew leaves for work, he locks her in the apartment. It’s an oversight — he didn’t intentionally make her a prisoner — but she feels like one. When she makes the foolish decision to walk in the neighborhood, she’s almost done in by the oppressive heat and shouted at by men through the windows of passing cars. Back in the apartment, she finds they share their living space with enormous cockroaches. And although the apartment overhead is empty, she hears mysterious footsteps walking its floors.

As time passes, Frances gets to know her neighbors and the other expat husbands and wives — while the mystery about what’s happening in the apartment above deepens.

In her previous life, our heroine Frances was a successful cartographer. Now she has nothing to do all day except visit with her neighbors and peek over the rooftop wall to watch life below.

The British women fare no better, passing their days like repressed 1950s housewives. They have two primary activities: grocery shopping — which they can only accomplish with their husbands as escorts when the men’s workdays are done — and hosting dinner parties with other expats. Those dinners are miserable, debauched evenings with too much bathtub wine, political arguments, one-upmanship, and near-constant conversations about money.

Drenched in Gothic atmosphere, this novel reads like Dame Hilary’s more literary take on a du Maurier-style thriller. Her storytelling is simultaneously suspenseful and languid. Her version of Jeddah is crushingly boring, far too hot, somewhat dangerous, and ultimately, impenetrable. And Frances is all of us, navigating the experience of being an outsider in a place meant to be home.

They have been out to dinner twice now, and to a party, and met a lot of people; they are becoming familiar with Jeddah cuisine, and with the strange but addictive taste of siddiqui and tonic. A telephone has been installed. The diary is kept less attentively, because her inner ear is attuned again to other people and the outside world. And yet, the first two weeks have changed her. Introspection has become her habit. There are things she was sure of, that she is not sure of now, and when her reverie is broken, and first unease and then fear become her habitual state of mind, she will have learned to distrust herself, to question her own perceptions, to be unsure – as she is unsure already – about the evidence of her own ears and the evidence of her own eyes. — Hilary Mantel

Wanna help us spread the word? If you like this page, please share with your friends.

Strong Sense of Place is a website and podcast dedicated to literary travel and books we love. Reading good books increases empathy. Empathy is good for all of us and the amazing world we inhabit.

Strong Sense of Place is a listener-supported podcast. If you like the work we do, you can help make it happen by joining our Patreon! That'll unlock bonus content for you, too — including Mel's secret book reviews and Dave's behind-the-scenes notes for the latest Two Truths and a Lie.

Join our Substack to get our FREE newsletter with podcast updates and behind-the-scenes info — and join in fun chats about books and travel with other lovely readers.

We'll share enough detail to help you decide if a book is for you, but we'll never ruin plot twists or give away the ending.

Content on this site is ©2026 by Smudge Publishing, unless otherwise noted. Peace be with you, person who reads the small type.