Armchair travel around the world!

Start your reading adventures with our FREE Reading Atlas.

- Around the World in 14 Books

- 7 Thrilling Book Series

- 6 Audiobooks That Are Like Theater For Your Ears

The Statue of Liberty is a beloved symbol of the promise represented by the United States. Beginning in September 1875, this enormous neoclassical lady welcomed immigrants to their new lives and new possibilities. But did you know she almost ended up somewhere else?

In a remarkable instance of 19th-century crowdfunding, Josef Pulitzer sponsored a campaign that placed the Statue of Liberty on her glorious perch above New York Harbor. He himself was an immigrant from Hungary who passed through a Lady-Liberty-less Ellis Island in 1864 (as a recruit for the Union army in the Civil War).

The Statue of Liberty was created by two Frenchmen as a gift to the United States from the people of France. She was designed by sculptor Frédéric Auguste Bartholdi, and her interior metalwork was built by Gustave Eiffel. She’s a depiction of the Roman goddess Libertas, and she is loaded with symbolism. In her right hand, she holds a torch aloft, lighting the way to freedom; in her left, a tablet inscribed with the date of the U.S. Declaration of Independence. And at her feet, she walks away from a broken shackle and chain to commemorate the abolition of slavery.

France funded the statue in its entirety. Then, in 1885, she was shipped to the United States, reportedly in 350 pieces packed into 214 wooden crates. She arrived on 17 June but soon found she had nowhere to go — plans were underway for a pedestal, but the $250,000 price tag (about $6.55 million in 2019) delayed her perch. The American Committee for the Statue of Liberty raised about half the needed funds, but both the state of New York and the U.S. Congress passed on covering the remaining costs. The Committee threatened to send her back to France, then made public appeals for donations in ‘any amount, however large and however small.’

But Americans outside New York balked at the idea that they should foot the bill. It was a ‘New York affair,’ said one Indianan, and another complained that the Committee was trying to entice ‘the people of Chicago and Connecticut… to pay the expense that those of New York would like to avoid.’

Soon other cities were trying to woo Lady Libert to their turf: Philadelphia, San Francisco, Boston, and Baltimore all offered up their parks. This Josef Pulitzer could not abide.

You probably know Pulitzer most readily from the journalism prize named in his honor. But he started his career in news-making in 1883 by purchasing the morning World newspaper, headquartered in New York.

The paper was struggling, losing about $40,000 a year. Pulitzer turned it around, increasing circulation from 15,000 to 600,000 — mostly by being a champion for the causes of the poor and focusing his sales on immigrant communities. He also combined ‘important’ reporting — exposés of corruption, investigative journalism — with publicity stunts, overt self-advertising, comics, sports coverage, women’s fashion, and illustrations. News also became entertainment.

When Pulitzer learned that his city was in danger of losing the Statue of Liberty, he started a campaign to engage New Yorkers in rescuing this physical symbol of what he thought America could be.

In his most famous editorial, he wrote:

The $250,000 that the making of the Statue cost was paid in by the masses of the French people—by the working men, the tradesmen, the shop girls, the artisans—by all, irrespective of class or condition. Let us respond in like manner. Let us not wait for the millionaires to give us this money. It is not a gift from the millionaires of France to the millionaires of America, but a gift of the whole people of France to the whole people of America.

And then he sponsored fundraisers — boxing matches, art shows, theater productions — and promised to print the name of every donor, no matter how small their donation, in the newspaper. ‘We must raise the money! The World is the people’s paper, and now it appeals to the people to come forward and raise the money.’

It worked! The World received donations from 125,000 people, totaling $102,000 (about $2.7 million in today’s dollars). About 90-percent of the contributions were less than one dollar. Leonard Bender of Jersey City gave ten cents, a kindergarten class in Iowa sent $1.35. In Buffalo, New York, Mayor Jonathan Scoville donated his entire salary of $230.

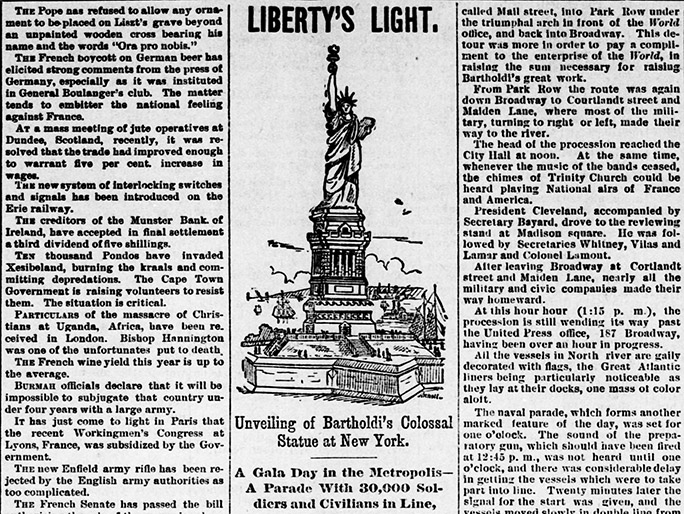

The Statue of Liberty, atop her pedestal, was officially unveiled and dedicated on 28 October 1886. More than one million people attended the festivities on the island and throughout the city, including her designer Frédéric Auguste Bartholdi. President Grover Cleveland, former New York governor, led a parade of firefighters, soldiers, and veterans — including 100 brass bands, cannons, and sirens — that marched through the city. The route started at Madison Square and wended its way to Battery via Fifth Avenue and Broadway, with a detour so it would pass in front of Pulitzer’s World building on Park Row. When the parade reached the New York Stock Exchange, traders tossed ticker tape from the windows, thus beginning the tradition of celebratory ticker-tape parades.

In the harbor, a naval parade of ships decorated in red, white, and blue sailed around Bedloe’s Island. When the French flat covering Lady Liberty’s face was dropped, cannons fired, and steam whistles blew from hundreds of ships.

It wasn’t all celebration, however. Women (except for the wife and daughter of two French envoys) were not permitted to attend the ceremony on the island; officials feared they’d be injured in the crush of people. Suffragists took umbrage and chartered their own boat to get as close as possible to the island. The group’s leaders protested against using a woman to symbolize liberty when American women couldn’t vote and advocated for their rights.

Not long after the dedication, The Cleveland Gazette, an African-American newspaper, argued that Liberty’s torch not be lit until the United States became a free nation ‘in reality.’

‘Liberty enlightening the world,’ indeed! The expression makes us sick. This government is a howling farce. It can not or rather does not protect its citizens within its own borders. Shove the Bartholdi statue, torch and all, into the ocean until the “liberty” of this country is such as to make it possible for an inoffensive and industrious colored man to earn a respectable living for himself and family, without being ku-kluxed, perhaps murdered, his daughter and wife outraged, and his property destroyed.

Regardless, the Statue of Liberty became a beloved landmark and was one of Pulitzer’s most meaningful accomplishments. In a few years, the statue’s dull copper color evolved to her iconic green patina. In 1903, a bronze plaque was mounted inside the pedestal’s lower level and inscribed with The New Colossus by American poet Emma Lazarus:

For more on Pulitzer’s fundraising campaign, you might like the children’s nonfiction book Saving Lady Liberty: Joseph Pulitzer’s Fight for the Statue of Liberty written by Claudia Friddell and illustrated by Stacy Innerst.

Top image courtesy of Tony Baggett/Shutterstock.

Want to keep up with our book-related adventures? Sign up for our newsletter!

Can you help us? If you like this article, share it your friends!

Strong Sense of Place is a website and podcast dedicated to literary travel and books we love. Reading good books increases empathy. Empathy is good for all of us and the amazing world we inhabit.

Strong Sense of Place is a listener-supported podcast. If you like the work we do, you can help make it happen by joining our Patreon! That'll unlock bonus content for you, too — including Mel's secret book reviews and Dave's behind-the-scenes notes for the latest Two Truths and a Lie.

Join our Substack to get our FREE newsletter with podcast updates and behind-the-scenes info — and join in fun chats about books and travel with other lovely readers.

We'll share enough detail to help you decide if a book is for you, but we'll never ruin plot twists or give away the ending.

Content on this site is ©2026 by Smudge Publishing, unless otherwise noted. Peace be with you, person who reads the small type.