Armchair travel around the world!

Start your reading adventures with our FREE Reading Atlas.

- Around the World in 14 Books

- 7 Thrilling Book Series

- 6 Audiobooks That Are Like Theater For Your Ears

Walking into a library is like stepping out of the slipstream of time. Past, present, and future commingle in the pages of books that have survived wars, floods, regime changes, and censorship. Those treasures may be shelved next to fresh-off-the-presses volumes that have yet to leave their mark on the world. From Europe to the UK and the US, these bookshelves have rich stories to tell and breathtaking settings in which to share them.

Built between 1723 and 1726, the Library has three main parts — two side wings and a cupola — divided by two’ pillars of Hercules’ that bear Charles the VI’s motto: Constantia et fortitudine. (By persistence and courage). Floor-to-ceiling bookshelves line the rooms, and some of them slide open to reveal hidden reading rooms called ‘star chambers’ — because the books kept on those special shelves were designated with a star. And everywhere you look, you’ll find gilding, statues, busts, twisting staircases, mosaics, frescoes, and leather-bound books. The Library also includes four oversized, gorgeously decorated Venetian globes — each is more than three feet (1m) in diameter.

This Library was the first library ever to be open to the public. The hours were 8 a.m. to noon, and the Emperor’s instructions to users were as follows:

Emporer Charles, son of the sublime Emporer Leopold, Augustus, has determined that this Library shall be for general use… The ignorant, servants, layabouts, gossipmongers, and idlers should keep out. Silence must be observed. Users should take care not to disturb others by reading aloud… Those using the Library need pay nothing; departing richer than when they arrived, they will return the more often.

The Austrian National Library houses more than 12 million books and objects — 200,000 of which have been digitized, so anyone can enjoy them free online via Google Books and Europeana. In person, the Library offers guided tours in German, English, French, Spanish and other languages – you can also tour the Library on your own. {more}

Located in Minsk, the capital, this is the largest library in the Republic of Belarus. In fact, it houses the biggest collection of books in the Belarusian language outside of Russia: about 10 million items, including more than 90,000 rare printed books and manuscripts dating from the 14th and 15th centuries.

Built between 2002 and 2006, the library is in the shape of a rhombicuboctahedron, a solid with eight triangular and 18 square faces. More than 90,000 citizens of Belarus are library users, and the library can accommodate up to 2000 readers within its 23 floors.

An observation deck is located on the building’s roof, overlooking the city of Minsk and the Slyapyanskaya waterway, a water system of canals and waterfalls that meanders through the city. In a park, just a few minutes away on foot, is a miniature replica of the Eiffel Tower.

In addition to the observation deck, the library also has a café on the twenty-second floor, and guided tours are available by request. {more}

The library was established shortly after the university was founded in 1425 and has had a tumultuous history. It lost its collection of rare books and manuscripts to France after the French Revolution — and then was burned by a German soldier during WWI. The flames o the fire devoured around 300,000 books, 800 incunabula (books printed before 1500), and 1,000 manuscripts.

Post-war, a new library with a bell tower was built with American support; the American flag is still flown over the building every 4th of July. But the library was ravaged again during the Nazi invasion of WWII. All but 15,000 volumes were destroyed by fire. Repairs began as soon as Belgium was liberated in 1944, and a new building was modeled after the old one.

Today, it’s a modern humanities library, and the main reading room is open to visitors. There’s also a 240-foot (74m) bell tower with a winding spiral staircase of 200 steps; the balcony at the top delivers bird’ s-eye views of Leuven.

The library offers audio (English, Dutch, French, German, and Spanish) and guided tours to visitors, carillon concerts, and climbs up the bell tower. {more}

The Strahov Library is made up of the Theological Hall, the Philosophical Hall, and the Cabinet of Curiosities. It holds more than 200,000 volumes in its collection, including first printings of more than 1000 books on the subjects of religion, medicine, mathematics, law, philosophy, astronomy, and geography — mostly in Latin, of course.

The Theological Hall, shown here, was built in the late 17th century. Its curved ceiling is decorated with baroque stucco and paintings depicting the theme of wisdom, along with the Latin words initio sapientiae timor domini (the beginning of wisdom is the fear of God). This room is infused with fresh, white light, perhaps sweeping the darkness of ignorance out of the corners and shadows.

In contrast, the Philosophical Hall (at the top of this post) is filled with warm light, reflecting a burnished glow from the floor-to-ceiling hand-carved walnut bookshelves and gilt trim. The room is made magical with spiral staircases in the corners and two secret passageways hidden by bookshelves (that can be opened via faux books).

The hallway leading to these rooms is a Cabinet of Curiosities that includes, among so many other treasures, a narwhal tusk, medieval weapons, a dendrology library, a 16th-century model warship, and more. {more}

This reading room — located in the neo-Gothic library — was designed to mimic the layout of a church, with a vaulted ceiling, a long center aisle through the ‘nave,’ stained glass in the ‘ambulatory,’ and high windows to let in natural light. The alcoves that line the side aisles are like miniature chapels, meant for private study.

Although this library bears the name of the man it honors, it was founded by a woman with a lifelong commitment to philanthropy.

Enriqueta Augustina (Rylands) was born in Havana, Cuba, in 1843; her father was originally from Yorkshire, England. As wealthy young ladies were wont to do, she was educated in New York, London, and Paris. Around 1860, she became the companion to Martha Ryland, wife of a wealthy merchant named John, in Stretford, England. When Martha shuffled off this mortal coil, Enriqueta married John. He was 74 years old. When he died thirteen years later, she inherited his estate, valued at £2,574,922.

In memory of her husband, Enriqueta established the library, and it was inaugurated on 6 October 1899, the anniversary of their marriage. She was committed to charitable works throughout her life and donated much of her wealth to educational and medical institutions. A statue of Enriqueta was commissioned by supporters of the library, and in 1907, a few months before her death, it was unveiled in the library she created.

The John Rylands Library exhibition galleries, reading room, collections, and more are open to the public. {more}

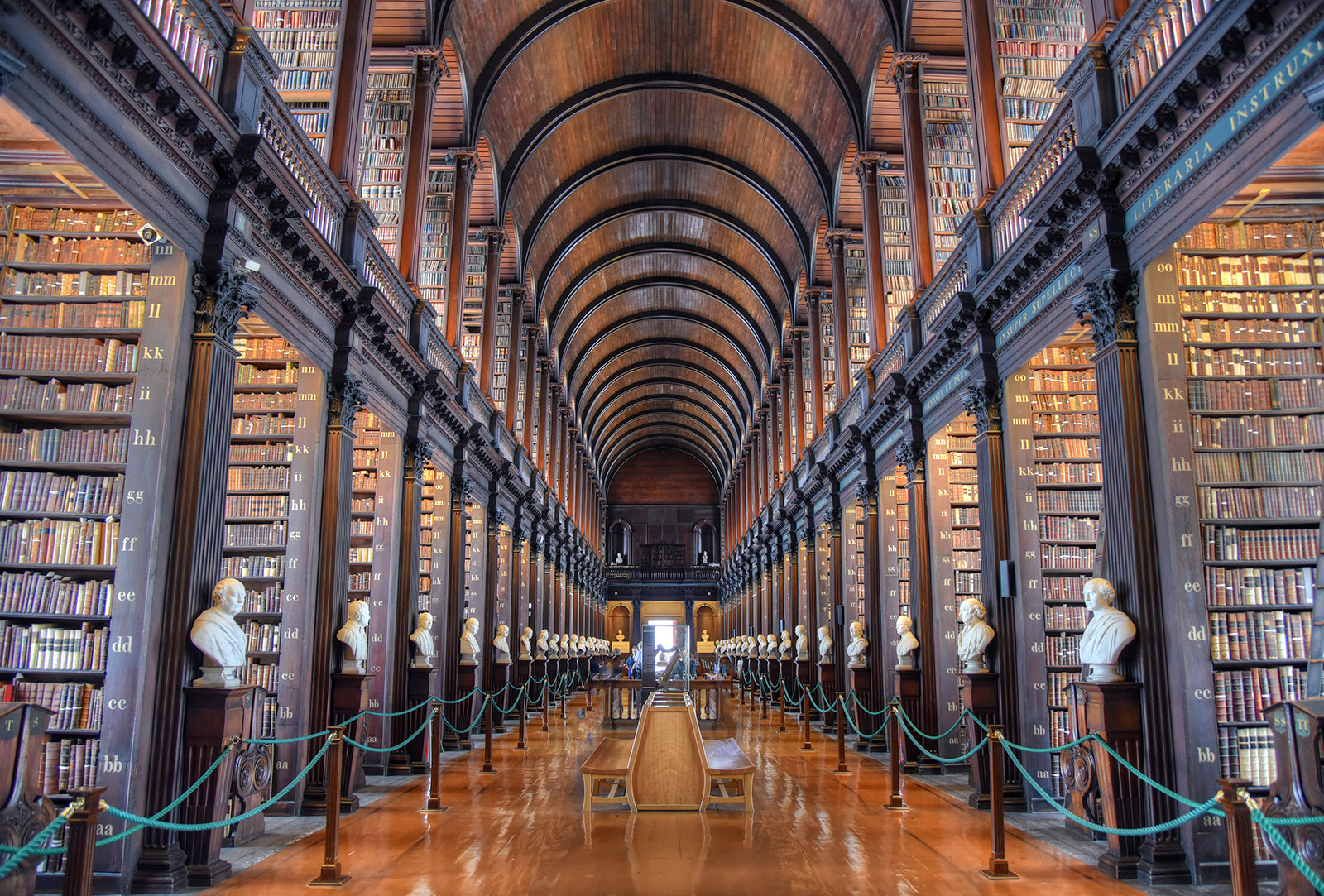

The Long Room was built between 1712 and 1732 and is the repository for the Library’s oldest books. Oak bookshelves stretch the length of the 213-foot (65m) long chamber, accompanied by 14 marble busts of great philosophers and writers, including Jonathan Swift, author of Gulliver’s Travels, among many other works of prose and poetry.

The Library of Trinity College is a copyright library, which means that all publishers in Ireland must contribute a copy of all of their output to the Library, free of charge. It’s also home to the Book of Kells, a beautifully illuminated manuscript of the Gospels in Latin dating back to 800 AD.

The Library is open to visitors; tours include an exhibit about the Book of Kells, other rare manuscripts, the medieval Brian Boru harp, the Long Room, and the Libary Shop. {more}

John Pierpont Morgan, a.k.a., J.P., was an American financier and banker who crushed it in the industrial consolidation and corporate finance game in America at the turn of the 20th century. But lest you think he’s just another rich white dude, remember this: When he died, his fortune was estimated to be $118 million, and almost half of it was tied up in his collections of art and books. He was a patron of both the American Museum of Natural History and the Metropolitan Museum of Art, and he created his remarkable library in the heart of Manhattan.

This two-story library is the platonic ideal for book lovers: golden light, frescoed ceilings, Persian rugs, and floor-to-ceiling books, including three Gutenberg Bibles and first editions by authors including Charles Dickens, Edgar Allan Poe, Herman Melville, and more. There’s even a collection of classic children’s books.

The library is home to 12,000 drawings from pre-1825 Europe; autographed musical scores from Beethoven, Brahms, Chopin, Verdi, and Mozart; the only manuscript of Milton’s Paradise Lost; and handwritten manuscripts from Sir Walter Scott, Lord Byron, William Makepeace Thackery, and Charlotte Brontë. {more}

Found in the city center, the National Library of Sweden is a research library, and it preserves all domestic printed and audio-visual materials published in the Swedish language. It also has plenty to recommend it to visitors, including this light-infused reading room that anyone is welcome to use for reading, studying, computer work, or daydreaming. There’s a cozy café in the lobby that offers the exact right level of people-murmur as background noise, so you can make a day of it.

But perhaps the most compelling reason to visit the library is the Codex Gigas, a.k.a., The Devil’s Bible. Created in the 13th century, it’s the world’s largest preserved manuscript from the Middle Ages. And experts believe all of its 600+ pages were written and illuminated by the hand of one unnamed Benedictine monk.

According to legend, a monk who broke his vows was sentenced to be walled up alive. He begged for clemency and promised to write a book that included all human knowledge — in just one night. At midnight, he realized he would never succeed in his task, so he prayed to the fallen angel Lucifer to help him. The devil delivered, so the monk drew the devil’s portrait on page 577 of his manuscript in gratitude.

In reality, one monk did write the entire book, but it took him approximately 25 to 30 years to complete it. The oversized book was initially kept at a monastery in Bohemia (now the Czech Republic) but was stolen by the Swedes during the Thirty Years’ War and taken to Stockholm as war booty in 1649.

Now the book is housed at the National Library in a climate-controlled case to protect it’s white leather binding adorned with fancy gewgaws. {more}

Top image courtesy of Jonathan Francisca/Unsplash.

Want to keep up with our book-related adventures? Sign up for our newsletter!

Can you help us? If you like this article, share it your friends!

Strong Sense of Place is a website and podcast dedicated to literary travel and books we love. Reading good books increases empathy. Empathy is good for all of us and the amazing world we inhabit.

Strong Sense of Place is a listener-supported podcast. If you like the work we do, you can help make it happen by joining our Patreon! That'll unlock bonus content for you, too — including Mel's secret book reviews and Dave's behind-the-scenes notes for the latest Two Truths and a Lie.

Join our Substack to get our FREE newsletter with podcast updates and behind-the-scenes info — and join in fun chats about books and travel with other lovely readers.

We'll share enough detail to help you decide if a book is for you, but we'll never ruin plot twists or give away the ending.

Content on this site is ©2026 by Smudge Publishing, unless otherwise noted. Peace be with you, person who reads the small type.